“Shall we see our children stripped of everything provided by a wise Providence for the sustenance of untold generations? The earth does not belong entirely to the present. Posterity has its claims.”

— Frank Lamb, Grays Harbor forester, 1909

Hardly a day goes by anymore without the release of a disturbing new article or study exposing the terribly destructive impact toxic herbicides are wreaking on our world. Just in the last few months, popular articles have linked common herbicides to autism, anencephaly birth defects, and an exceptionally deadly outbreak of kidney disease in Central America. In that same time, a study published in the journal Biomedical Research International revealed that Monsanto’s Roundup herbicide is 125 times more toxic than regulators say; a feature in The New Yorker described how large chemical manufacturers like Syngenta systematically harass scientists for producing research that threatens their profits; and the Seattle Times ran an editorial entitled “The Failure of the EPA to protect the public from pollution” which documents the chemical industry’s cozy ties to government regulators.

In this context, the battle to defend our wildlife populations in the Pacific Northwest from the known dangers of forest chemicals is but one front in a global war on this most pervasive and insidious toxicity. Our elk herds, suffering as they are from multiple maladies including an epidemic of hoof disease, are simply the largest and most obvious victims of a prolonged siege that is being waged on industrial timber lands throughout the states of Washington and Oregon. Thankfully, just as Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) officials began informing the public of their intention to euthanize crippled elk before actually understanding the cause of their disease, the collective rallying cry to save these animals, or at least properly study them, has become very loud indeed.

On July 15th, Clark County Commissioners unanimously approved a resolution requesting that the Washington legislature and Governor Jay Inslee direct WDFW and other agencies to “study the effects of herbicide application on our state forest land before culling elk and determine whether the state’s forest practices are, on balance, enough to protect our natural environment, specifically our wildlife resources.”

Ten days earlier, State Senator Don Benton addressed a letter to members of Washington’s Forest Practices Board, encouraging them to “re-examine the practice of saturating clear-cuts with thousands of pounds of herbicides and examine the possible negative impacts this practice has on our citizens and our natural resources.”

Members of the Forest Practices Board, a rule making body charged with protecting the state’s natural resources while maintaining a viable timber industry, had assembled for a special meeting on July 8th to consider a petition filed by activist Bruce Barnes hoping to reduce aerial chemical sprays. Though the petition was denied due to a lack of bureaucratic jurisdiction, and responsibility punted on to the Department of Agriculture and WDFW, members of the Forest Practices Board appeared troubled by the brief public testimonies they heard that morning.

“I appreciate that you’ve brought this issue to our attention,” said Dave Herrera, a general public Board member and longtime Skokomish tribal leader. “The animals that we are talking about are in fact treaty resources. And so the tribes have a huge interest in making sure our treaty resources that our ancestors protected for us continue to be here for us to use.”

Board member Dave Somers, a Snohomish County Councilman, added, “I encourage DNR and [the Dept. of Agriculture] and WDFW and others to keep working on this and make sure that they’re casting a broad net and that they’re looking at this close until we get some more definitive answers on whether or not herbicides or other forest chemicals might play a role in this.”

Along with support from high-ranking government officials, some of the local news outlets have recently joined in to question the role herbicides may be playing. “Are chemicals causing elk hoof disease?” was the title of the July 15th KOIN 6 coverage of the Clark County Commissioner’s resolution. “Are herbicides to blame for region’s hoof rot woes?” read the headline of an excellent Longview Daily News feature published that same day. More definitively, “Don’t let timber firms call shots on hoof rot,” ran a TDN editorial on July 20th.

A thorough series of investigations into the impact herbicides are having on elk hoof disease and other sources of wildlife declines now looks promising, and these studies may even be free from the intentionally misleading “science” routinely paid for and peddled by the timber and chemical industries. This outcome, however, was not, and is not, inevitable. Elk hoof disease has been observed in southwest Washington for twenty years, and it was only because a core group of hunters and conservationists like Bruce Barnes and Mark Smith kept pushing this issue so doggedly that the tide is finally turning in favor of the health of many over the profits of a few. Their relentless pursuit of the truth, and their willingness to fight for the well-being of those creatures that do not have a vote or a voice, must continue to prevail and to inspire others if we are ever going to restore the health and balance of our forests and all the people and plants and critters that dwell there.

On June 23rd, WDFW officials sent out a press release announcing their plans to euthanize elk with severe symptoms of hoof disease.

“At this point, we don’t know whether we can contain this disease,” said Nate Pamplin, Director of WDFW’s Wildlife Program, “but we do know that assessing its impacts and putting severely crippled animals out of their misery is the right thing to do.”

This selective culling or euthanasia program is based on WDFW’s assertion that a 16-member scientific panel they had assembled on June 3rd was in agreement that the disease most likely involves a type of bacterial infection closely resembling ovine digital dermatitis in sheep and associated with bacteria known as treponemes. Because there is currently no vaccine for this disease, and no proven options for treating it in the field, WDFW’s official line is that “the diagnosis limits the department’s management options.”

Critics, however, question the timing and logic of this culling program, and wonder why it is only now, after two decades of hoof disease, that WDFW officials are showing their concern for putting severely crippled elk out of their misery.

“There are too many unanswered questions,” said Mark Smith, a member of WDFW’s Elk Hoof Disease Public Working Group. “They haven’t been able to solve the problem, and now they’re trying to eliminate the problem.”

Taking it one step further, Barnes said, “I think they know it’s these chemicals and they’re covering it up.”

Regardless of whether one has a taste for conspiracy theories, WDFW’s culling program relies upon the tenuous assumption that elk hoof disease is infectious and not environmental, hence the need to contain it before it spreads even further. As it is still unknown whether the disease is infectious, critics have pointed out that killing affected elk is essentially squandering opportunities for live studies, something WDFW has been extremely resistant to, and which continues to fuel accusations that WDFW has been actively covering the tracks for the timber and chemical industries.

“A captive elk herd is a no-brainer,” said Bob Schlecht, owner of Bob’s Sporting Goods and another member of WDFW’s Elk Hoof Disease Public Working Group.

Mark Smith has even gone so far as to offer to enclose elk at his Eco Park Resort east of Toutle. “They don’t study cancer on dead people,” he said. “You study disease in live organisms.”

Smith has offered to coordinate an independent investigation into the effects herbicides might be having on the health of local elk – and at no additional expense to taxpayers. He even has scientists and volunteers willing to donate their time and expertise, also for free. At a special meeting in Olympia, Smith’s offer was rejected by WDFW Director Phil Anderson on the grounds that since his department was so close to understanding the cause of the disease, Smith’s generosity was unnecessary. Now it appears that WDFW would rather euthanize elk than move a few of them to Smith’s property and see if mineral blocks, a hoof trimming and an herbicide-free environment alone might improve their condition.

There are other reasons to doubt the wisdom of the proposed culling program, not the least of which is that despite the confidence WDFW is projecting, perhaps half of their 16-member scientific panel expressed serious misgivings about the diagnosis that is currently being sold to the public.

“You’re mentioning lots of different bacteria. That’s one piece of the puzzle,” said Dale Moore, an expert in preventive veterinary medicine at Washington State University, “but there are other things that seem to be missing in the puzzle. Big pieces. The big pieces are the environmental factors and why this particular region and not other regions.”

Echoing the sentiment shared by most observers, Dr. Paul Kohrs, Acting State Veterinarian with the Department of Agriculture, stated that “something must be done different down here with forest practices,” adding that “It needs to be explored.”

Even WDFW’s lead investigator, veterinarian Dr. Kristin Mansfield, is still finding it challenging to explain how this supposedly infectious disease is transmitted, along with why the elk only recently began finding themselves susceptible to these bacteria.

“It’s believed that the wet environment, as you would find in a dairy, help perpetuate the disease,” Mansfield told the Forest Practices Board on July 8th. “I just felt that the tissue needs to be damaged by being wet part of the time before the bacteria can penetrate. And it’s interesting that – not surprising perhaps – that if this disease were to show up in elk, it would be one of the wettest parts of the state, where the ground is frequently wet.”

“But the wetness isn’t a new thing,” responded Board Chairman Aaron Everett.

“No, it’s not,” Mansfield said as a few titters from Board members were audible.

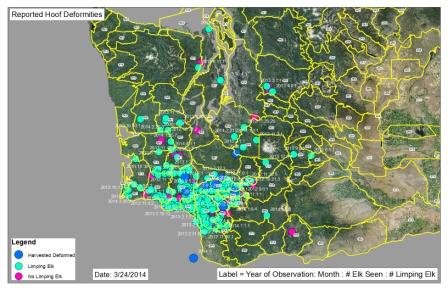

While the dampness of western Washington might yet prove to be a factor, it is hard to fathom that its role is in any way central to this disease. Elk have evolved over many millennia to thrive in this sodden environment, while throughout the Olympic Peninsula, one of the wettest places in the world, there has not been a single documented report of ‘hoof rot’ according to WDFW’s own hoof disease observation map.

When listening to Dr. Mansfield’s presentations, several keen observers have shared their impression that it’s as if she’s resorting to scientific hail marys while simultaneously overlooking or even ignoring vital aspects of this case which most reasonable epidemiologists would have long ago considered at length. Perhaps certain questions or subjects have been deemed off-limits by her superiors and constrained the range of her hypotheses. Whatever the reason, Dr. Mansfield seriously misled the Forest Practices Board on one consequential topic.

“We’re feeling very comfortable that the disease is limited to the hooves,” Mansfield declared. “It is not involving any other part of the body.”

This notion that the disease is limited to the hooves helps support WDFW’s current assessment that ‘hoof rot’ is a treponeme-associated bacterial infection and not something more systemic. The notion, however, is patently false. As numerous citizens and Public Working Group members have pointed out at multiple meetings in which Mansfield has been in attendance, antler deformities are commonplace and disproportionately affecting elk with hoof disease.

At the most recent Hoof Disease Public Working Group meeting in Kelso on May 21st, Clark County Senior Policy Advisor Axel Swanson said, “At the town hall there was a lot of talk about deformed horns. We’ve got a lot of reports and videos and pictures of weird looking horns along with this issue. They’re growing down, they’re growing sideways. I don’t know if we’ve looked into that any more or heard any more?”

Mansfield replied, “I’m not getting that with the antlers. I’m not saying it’s not happening, but it’s not making it to my email or desk. So I don’t know how to respond to that.”

While after five years of investigating elk hoof disease, Mansfield is still “not getting that with the antlers,” a thread on the hunting-washington forum entitled “SW Washington Deformed Antlers” shows pictures of nearly 20 elk with antler deformities associated with hoof rot and has thus far garnered more than 2,000 views.

One commenter wrote, “I’ve looked at over 50 bulls that have been killed and had hoof rot from the Willapa Hills area. Over 95% of them have had a horn deformity on the opposite side from the hoof rot.”

Another wrote, “I was at the meeting and when they declared that they haven’t seen any antler deformity associated with hoof rot I about fu*kin puked. I realized we (I mean they) are farther out of touch than I thought.”

Later I will explain why hoof and antler deformities may be so commonly linked, as well as how they may be related to forest chemicals, but for now I wish to use this huge lapse in epidemiological skills to demonstrate why so many people distrust the integrity of WDFW’s investigation, and why most will continue to distrust WDFW until their leadership is overhauled.

The next official WDFW assertion that needs refuting is that elk hoof disease is restricted to southwest Washington. As of the date of this publication, WDFW’s website contains a page that lists a series of frequently asked questions relating to elk hoof disease. The 14th and final question reads: Are herbicides a likely cause of hoof disease? Their answer:

“There is no scientific evidence that chemicals can cause this kind of disease in animals, and no link has been made between herbicides and hoof disease in any species that we are aware of. Timber companies use similar herbicide treatments along the West Coast, yet elk populations in other areas have not exhibited the symptoms associated with hoof disease seen in southwest Washington. The University of Alberta and the National Council for Air and Stream Improvement (NCASI) are currently examining habitat characteristics of the landscape and areas used by elk, which may help to inform our understanding of this issue.”

It seems almost redundant by now to point out that NCASI scientists are funded by a consortium of timber companies while the University of Alberta study was funded largely by a combination of chemical and timber companies. More salient is WDFW’s official claim that “elk populations in other areas have not exhibited the symptoms associated with hoof disease seen in southwest Washington.” Similar to their misleading statements about antler deformities, their claim that hoof disease is restricted to southwest Washington helps support the infectious bacterial cause they have been selling, and just like antler deformities, it is a fallacious statement they have had ample opportunity to correct.

The simplest way to rebut WDFW’s claim that elk hoof disease has not been observed outside of southwest Washington is to direct them to a February 27th, 2013 article in the SnoValley Star that begins, “Elk hoof rot, a disease seen predominantly among elk in Southwest Washington, has found its way to the Snoqualmie Valley herds.” According to Harold Erland, a wildlife biologist with the local Elk Management Group, three Snoqualmie Valley elk were found with the condition. Two of the elk expired right in the town of North Bend while a third was struck by a vehicle and later found dead at Snoqualmie Middle School.

“Saw one drop dead myself just outside of town,” wrote a commenter on a hunting-washington thread devoted to the issue. In a personal message he later told me that the elk died in front of him near Chinook Lumber in North Bend, adding that he had since seen one other in the valley.

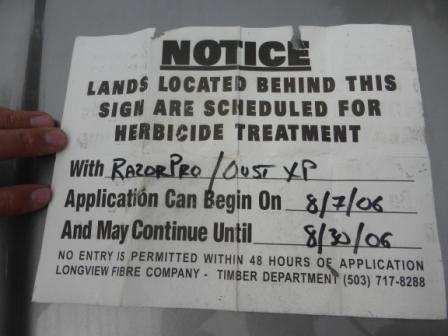

For those unfamiliar with Washington’s geography, it is about 100 miles as the crow flies from southwest Washington to the Snoqualmie Valley. While elk herds surely do commingle, and bacteria could feasibly be spread that far, it is important to note that much of the forested land north of the towns of Snoqualmie and North Bend is currently owned and operated by industrial timber companies that regularly employ herbicide sprays similar to those in southwest Washington. In fact, a survey of the area using google’s satellite maps feature shows many clear cut parcels which upon further inspection appear the lifeless brown color so commonly associated with defoliating techniques used by timber companies to reduce vegetative competition. Although “nuked” clear cuts may only constitute 5% or less of the elk’s home range, these open areas are also where elk typically feed, and where they are likely ingesting high doses of forest chemicals.

Additionally, as WDFW Regional Wildlife Manager Sandra Jonker explained at the Working Group meeting on Feb. 12th, radio-collared elk in western Washington have demonstrated that they do not move around a great deal but typically stay within a surprisingly limited area. While it is possible that these sick, limping elk migrated many miles from southwest Washington, crossed the I-90 freeway, and passed through bustling population centers, it seems more likely that the elk in Snoqualmie are developing ‘hoof rot’ right there in the valley where they reside. Each of the Snoqualmie Valley elk with ‘hoof rot’ were found on the north side of town, opposite from I-90, and within easy walking distance from bald, brown clear cuts.

Moreover, reports of limping elk are conspicuously absent from Mount Rainier National Park despite receiving nearly two million visitors each year, and despite being within a hypothetical migratory route from southwest Washington to Snoqualmie. In fact, out of the hundreds of reports of limping elk in western Washington, not a single one shows up in any of the three National Parks on WDFW’s hoof disease observation map – a strong indicator that where natural conditions are intact and forest chemicals are largely absent, elk maintain normal ambulation.

It remains to be seen if elk hoof disease in southwest Washington and the Snoqualmie Valley are related or are instead occurring independently of each other. For now, it is more important to understand very clearly that WDFW’s assertion that elk hoof disease is relegated to southwest Washington is most flagrantly false. In all the meetings I have attended on the subject, not a single WDFW employee has ever brought up these ‘hoof rot’ elk in the Snoqualmie Valley, nor are they mentioned on WDFW’s website or in any of their studies or publications. It seems to many observers that WDFW has failed to investigate a crucial component of the case; namely, what these separate elk populations may have in common environmentally.

But there are other places where elk appear to be suffering from hoof disease and these are even more challenging to fit within WDFW’s infectious bacteria theory. They also require the crossing of a very big river. ‘Hoof rot’ has now been reported in at least 6 counties in Oregon, some as far south as the Dean Creek Wildlife Area which is closer to California than Washington.

“Several winters ago… I observed half or more of the herd at Dean Creek limping with signs of hoof rot,” wrote one commenter on the popular ifish forum who later confirmed his observations with me in personal correspondence.

Another commenter later corroborated this sighting, saying that a few of the elk had the telltale curly hooves, as well as tiny deformed horns that are so often associated with elk suffering from hoof disease.

When I asked the original Dean Creek commenter if he had any other experiences with elk hoof disease he responded that a coworker of his shot a bull that had “all 4 hoofs so overgrown we couldn’t believe that he could even walk! It was really amazing, and slightly disturbing. They were 5-6 inches longer in the toe than I have ever seen and curled over inward.” When I asked him when and where the bull was shot, he replied that it was probably three years ago “on the divide between the Umpqua [National Forest] and the Willamette above the Hills Creek Reservoir.” In other words, smack in the middle of industrial timber country, and in an area that environmentalists complain is overly logged and rife with clear cuts.

The mainstream press is now picking up on this scent and recent news reports have all but confirmed that ‘hoof rot’ is indeed afflicting elk in the Beaver State. ODFW veterinarian Dr. Julia Burco has said that two hoof samples hunters took in Multnomah and Clackamas counties closely resemble elk hoof disease, and according to The Oregonian, “Several other cases have been reported, but not yet evaluated.” All that remains is a survey to determine just how widely the condition can be found in Oregon.

In early June, my brother Tim (a Clark County Deputy Sheriff) received a tip that if we wanted to prove that ‘hoof rot’ was in Oregon we should go hang around the Weyerhaeuser property east of Tillamook. According to the source, the elk there were in very poor shape, and ODFW had been selectively and covertly culling individuals suffering from ‘bacterial leg deformities’ as they were reportedly referring to it. Excited by the prospect of obtaining video footage that could prove that elk ‘hoof rot’ was indeed present in Oregon, Tim and I spent a day investigating the woods around Tillamook to no avail. In fact, we didn’t spot a single elk the entire day.

However, as we were returning home along the coast Tim had a hunch about a particular road just southeast of Seaside. He slowed the truck as we spotted two men in waders cleaning fish in their driveway, the garage behind them adorned with a rack of horns. Tim pulled into the driveway and asked the men how the elk in the area were faring.

“What are you asking for?” one of the men replied.

Tim briefly explained our mission and asked, “Have you seen any elk that might be sick or showing signs of limping?”

The man shifted his weight. “What do you know about herbicides?”

The man’s name is Bill Teeple and he explained that he was the former owner of a sporting goods store in Seaside. Because of the store he found himself deeply involved with local fish and game management over the years and often “locked heads” with ODFW employees.

“I fought em,” he said with gusto. “I had cops following me around the woods trying to get me on a game violation. I had one game cop going in my house looking in my refrigerator. I tell you what, they don’t play fair.”

Similar to the concerns held by many hunters and conservationists in Washington, one of Teeple’s biggest beefs with ODFW administration is their ongoing alliance with the timber industry and seemingly at the expense of the wild game populations they are tasked with managing.

“My feeling about it is that any time you have the state in the tree business you’re fighting a losing battle,” he explained. “The state agencies are really in trouble financially. The game commission doesn’t want to cause any waves because they’re in bad financial straits.”

Teeple also shared his deep distrust of herbicides.

“I’ve maintained that we’ve had a problem with herbicides for years and years,” Teeple declared. “It’s horrible smelling. You wouldn’t catch my ass within a quarter mile of where they’re spraying that stuff.”

“Do they spray herbicides around here?” I asked him.

“You gotta be kidding.”

He walked me to the end of his driveway and pointed at a ridge a few miles in the distance.

“You see that clearcut right there? They cut that eight years ago. For four years running they sprayed it. It was brown. Their policy is they spray stuff until the tree gets big enough that it doesn’t have to compete.”

“They didn’t research none of that stuff,” Teeple said. “They just started spraying it.”

Teeple then told a story about hunting in an area nearby.

“This elk come into us, you know, and I shot it. It was at dusk. When he come in he looked fine. Then when we walked up to it, I shined a light across his body and his hip was sticking out real funny. You know, like it was winter. When I got up to him I noticed his ribs were all sticking out. When I opened him up we pulled the heart and lungs out. One lung was as black as your belt and the other lung was kind of a funky looking color and it had pus nodules around it.”

He followed this up with another disturbing story about an area that had been recently sprayed.

“Last year I was across the road from Saddle Mountain in the Wilson unit. It was during archery. This herd of elk I was in was physically coughing. And I’ve never, ever heard that before in my life.”

“In Clatsop County is one of the best herds of elk in the state of Oregon,” Teeple continued. “People come here from all over to hunt the Saddle Mountain unit. Last year and the year before I haven’t seen one herd with more than fifteen animals in it.”

“We’re lucky if we see threes and fours,” my brother lamented.

“It’s a hell of a mess,” Teeple agreed.

Teeple’s testimony is more than just a relevant anecdote. Only a few miles from where he reported hearing the elk herd coughing so unusually, others were claiming that dozens of elk had recently died from a parasite known as lungworms.

“I have heard 35+ dead elk around the Jewell refuge,” wrote one commenter on an ifish forum thread. “ODFW is being very quiet… heard lung worm but no real info yet.”

“I was surprised at how few elk were using the refuge this winter,” said another ifish commenter about Jewell Meadows. “Hadn’t been there in quite some time but remember years ago, it was pretty well populated. Seems to be down a good 60%, maybe more. The remaining animals look to be in poor shape.”

Curious about these rumors, I called the manager of the Jewell Meadows Wildlife Area, a refuge managed by ODFW, and he confirmed that it was true – a large number of local elk had in fact died of lungworms recently. When I asked him if it was possible that these lungworm deaths could partially be attributed to herbicides, he told me that he wouldn’t even speculate. He assured me that lungworms are naturally, if not commonly, contracted by animals, and when I asked him about Teeple’s report of a herd of coughing elk nearby, he replied that perhaps they had all just got done running. Finally, I asked him if any of the timber companies had any holdings in the area and he said, yes. Weyerhaeuser was present and actually owns some of the land within Jewell Meadows.

Using google maps, one can see for themselves just how intensively managed the industrial timber land is around Jewell Meadows. It would be challenging to even count the number of clear cuts in the immediate area, and one can only speculate on the extent of the impact saturating preferred feeding grounds with chemicals must be having on the local elk.

While anecdotal correlations between coughing elk, herbicide sprays and death by lungworm may be summarily dismissed by critics, what cannot be ignored is the array of reputable studies linking herbicide exposure to weakened immune systems and an increase in bacteria and parasites. One of these studies, published in 2003 in the international, peer reviewed journal Oecologia, found that lungworms were “significantly accelerated in hosts exposed to the highest concentrations of pesticides, leading to the establishment of twice as many adult worms in the lungs.”

In this study, researchers exposed frogs to a pesticide mixture composed of, among other chemicals, atrazine, one of the most commonly applied forestry herbicides in the Pacific Northwest. The researchers found that the lungworms “matured and reproduced earlier in pesticide-exposed frogs compared to control animals” and that “such alterations in life history characteristics that enhance parasite transmission may lead to an increase in virulence.” Most importantly, the researchers stated that “certain components of the frog immune response were significantly suppressed after exposure to the pesticide mixture.”

It is this reduction in immune system strength brought on by exposure to herbicides that has so far seemed the most plausible route from forest chemicals to elk hoof disease. Immune suppression is still an important factor to consider; however, there now appears to be another pathway, one which encompasses antler deformities and much of WDFW’s existing research on hoof disease.

If you take the time to read a pair of elk hoof disease research articles jointly published by Kristin Mansfield and Sushan Han of Colorado State University, you will find that they write a great deal about mineral deficiencies, even going so far as to state that “possibly our most important finding in this study is marked copper and selenium deficiency in this population of elk.” Both of the articles are based on a 2009 study conducted in southwest Washington where 8 female adult elk were shot, necropsied, and then analyzed in an attempt to better understand the source of elk hoof disease. One of the articles was published in the April 2014 issue of the Journal of Wildlife Diseases and both of them are full of the word copper. Han and Mansfield write:

“Copper in particular is known to be vitally important for proper bone and keratin development. A. Flynn described in 1977, populations of Alaskan moose with similar severely overgrowth of hooves [sic]. The cause of this lesion, described as “slipper foot”, was not definitively determined; however, affected moose were found to be significantly deficient in copper. Copper deficiency in domestic cattle is known to be associated with an increased incidence of foot rot, heel cracks, and sole abscesses. Whether copper deficiency alone can induce or predispose hoof deformity in the Cowlitz basin elk, or if copper deficiency is one contributor to a multi-factorial problem, remains yet to be determined.”

The world’s scientific literature includes many examples of copper deficiencies causing keratin irregularities. Keratin is a protein which is the key structural component of hooves, hair, beaks and horns, among other things. Keratin irregularities result in an array of deformities in numerous species including a recent and dramatic increase in beak deformities in crows, chickadees and dozens of species of raptors. Keratin irregularities may even be a factor in deer hair loss syndrome, another controversial wildlife disease under WDFW management. Han and Mansfield go on to write:

“Copper is a vital component of keratin, and deficiency may lead to abnormal sulfur cross-linking, resulting in defective hoof keratin, but generally also defective antlers and hair coat, which was not identified in this study or in affected elk in this region in general.”

Contrary to findings in Han and Mansfield’s limited study, dozens of hunters have reported and shared pictures of severe antler deformities in the very same elk that are suffering from hoof disease. One possible answer for why these seemingly unrelated deformities may be so closely associated was already furnished by Han and Mansfield – copper deficiencies. But that of course leads to another question: Why are the elk copper deficient? And the answer to that question brings us back once again to herbicides.

According to Don M. Huber, a Professor Emeritus of plant pathology at Purdue University, U.S. agriculture has converted over the past few decades to an herbicide program focused around glyphosate, or Roundup, one of several trade names in which the chemical is considered the active ingredient. Industrial timber, which is a form of agriculture, has become dominated by similar practices. In a recent elk nutrition study conducted by researchers from the University of Alberta, they note that herbicide mixtures are variable but that “a typical site preparation might include an aerially applied treatment of 1.5 quarts glyphosate and 3 ounces of sulfometuron methyl in 10 gallons of solution per acre.” Examination of nearly any local spray notice will list glyphosate under one trade name or another.

In a 2012 paper concerning herbicides, Dr. Huber points out that glyphosate is a strong metal chelator and was first patented for that purpose by Stauffer Chemical Company in 1964. The process of chelation is complex and challenging to describe, but essentially it results in the binding of metal ions. This sounds innocuous enough, but chelation has the ability to strip the food chain of essential minerals, including copper (Cu). Dr. Huber writes:

“The introduction of such an intense mineral chelator as glyphosate into the food chain through accumulation in feed, forage, and food, and root exudation into ground water, could pose significant health concerns for animals and humans and needs further evaluation. Chelation immobilization of such essential elements as Ca (bone), Fe (blood), Mn, Zn (liver, kidney), Cu, Mg (brain) could directly inhibit vital functions and predispose to disease.”

Along with diminishing the quantity and quality of forage, and weakening immune systems, herbicides may also account for the documented mineral deficiencies that are known to cause both hoof and antler deformities.

Dr. Huber offers a band-aid type solution only realistic for domestic animals, stating that, “The lower mineral nutrient content of feeds and forage from a glyphosate-intense weed management program can generally be compensated for through mineral supplementation.” Though this practice might save a few individuals, WDFW is probably correct in their official statements that supplemental feed will not cure these animals. And if it is true that one or more pathways are leading from herbicides to elk hoof disease, then activists may also be right that the only effective remedy is a moratorium on herbicide sprays.

Despite all of the circumstantial evidence I have laid out in this article, it would be irresponsible of me to say that I have definitively proved herbicides are the cause of elk hoof disease. Far from it. Instead, my goal has been to provoke concerned readers to see beyond or beneath the official story presented by WDFW and others, and to provide future researchers with some potential routes forward. As Cascadia Wildlands Director Bob Ferris put it so elegantly in another article dedicated to this subject, “These are not ‘proofs’ in the traditional scientific sense but rather concrete rationales for further investigation – in short these are the building blocks of testable hypotheses.”

My hope now is that individuals much more qualified than I will pick up this torch and see what it illuminates.

My ongoing investigation of elk hoof disease and toxic forest practices is funded entirely by my readers. If you appreciate my work and believe that journalism should be fearlessly independent of corporate influence, then consider clicking on the donate button below so that I can continue giving these issues the time and attention they deserve. Thank you for your support.

Pingback: Big game and pesticides - Utah Wildlife Network

This is a really sad situation – it’s a shame that the Elk are suffering so much. Their pain and deformities are heart wrenching. I wonder how many other species of animals have been impacted in the areas that have had herbicide treatments ?

I am hopeful that Governor Inslee will initiate a thorough investigation of the herbicide use in Washington’s forests and timberland.

Thanks for bringing this situation to our attention. I look forward to your ongoing investigative reporting.

Scary to say the least. Anecdotal evidence is what often starts the trail of investigation. I was there when AIDS broke out on Portland, OR in 1981. I was working at Legacy Good Samaritan Hospital and Medical Center. We did not run from our patients nor call for the euthanasia, but engaged them in treatment while scientists started studying. Do we have histological investigation of the types of cell and tissue damage done by these different categories of herbicides? Epidemiological studies need to continue. The fact that these are “Treaty Resources” means that there is a higher authority than the WDFW or ODFW. Does the corporate charters of the timber companies give them the authority to break Indian Treaty Law? Consult your Secretary of State’s office and ask for a copy of the corporations involved corporate charter and compare it against their actions, same for laws setting up the WDFW/ODFW, are their actions congruent with their stated mission statement? Whose land is it under law? Have the treaties, actually been ratified by the US Senate? Do they give permission for negligence, public nuisance, endangering public health,human rights violations, and genocide? Have corporate officers been allowed to hide behind “limited liability corporation”?We’re still a Republic and the people remain in charge. Do not be intimidated/threatened by state or corporate operatives. To inform your self more about where we stand in reference to the unelected state officials, corporations, corporate officers, go to the Program on Corporations Law and Democracy (POCLAD). Read their pamphlet “Taking Care of Business” The American Revolution was against corporations, but the state and corporations want us to forget that. If you can try and get a copy of Francis A. Boyle’s “Defending Civil Resistance Under International Law” He give us a matyrix of

Boyle gives us a matrix of International Law, Indian Treaty Law, Constitutional law, and US Supreme Court decisions This is what we used to help the Western Shoshone Nation stop nuclear weapons testing that has contaminated their land in violation of the 1863 Treaty of Ruby Valley. That was a treaty between the Western Shoshone Nation and the United States. Under Article 6 Section 2 “all international laws and treaties are the supreme law of the land, local judges rulings notwithstanding” The Paque Habana, US v. Pink, US v. Belmont are a few cases you can review in Boyle’s book to apply to this situation. Is the Chinook Nation still the true owner of the land, if treaties were never ratified? Does that give them standing to take negligent state governments and corporations to national and international forum’s for judicial review? State administrative agencies must submit to international law. You always ask “Quo warranto” by what authority do you act? That can be tracted back to state law, state constitution, USSC decisions, US constitution, international law, and Indian Treaty Law. I saw about 10,000 from around the world arrested for walking into the Nevada Test Site, by Western Shoshone invitation with permits and never prosecuted, by the US.

Great information. The historical & prospective perspective adds even more gravitas to this abominable act against the Elk, our environment and our current and future generations.

Jon, keep up the good work of shedding the light of truth on this despicable & immoral attack through the improper & unethical use of pesticides for corporate profit.

If weyerhaeuser wasnt greasing the states pockets you might see some action on the hoof rott matter. who ever reads this, atrazine is your problem. remember the erin brockovich movie..

Pingback: Yakima Herald Outdoors Editor Praises Elk Investigation

Pingback: Editor of NW Sportsman Magazine Supporting Herbicide Study

I do believe that Timber companies, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife and the state of Washington have ruined my outfitting Business that I’ve had for over 20 years.

Jon

I wanted to give you my take on deformed antlers.

When an elk or deer is wounded on one side of its body either by hoof rot, gunshot wound or hit by a car the antler on the opposite side from the wound usually grows funny.

I have been living in the woods for 30 + years and after this year’s hunting season I finally was pissed off enough to write a website hoping someone would read it and do something about the problem. I didn’t even know how to build a website until 2 weeks ago.

This weekend I found your site and found out I’m not alone. Check out my site it’s still a work in progress.

washingtonelkanddeerfoundation.com

I can also be reached at: mik@alwayshunting.net

360 470 8708

Thanks for your work on this issue, Mike. Keep fighting and writing and feel free to reference my reporting as you wish.